By Steven Pink: The big puncher has always held a special place in the heart of the boxing fan. Since the inception of the sport, boxing’s concussive hitters have drawn the crowds, provoked expectations and thrilled audiences the world over. Anytime a renowned knockout artist steps into the ring a palpable frisson of excitement is to be expected. Boxing remains the only sport where a seemingly unassailable lead can be rendered obsolete in the blink of an eye.

By Steven Pink: The big puncher has always held a special place in the heart of the boxing fan. Since the inception of the sport, boxing’s concussive hitters have drawn the crowds, provoked expectations and thrilled audiences the world over. Anytime a renowned knockout artist steps into the ring a palpable frisson of excitement is to be expected. Boxing remains the only sport where a seemingly unassailable lead can be rendered obsolete in the blink of an eye.

Nothing keeps a boxing fan on the edge of their seat more readily than the thought of a brutally conclusive ending. Artistry and panache, ring generalship and defensive flair draw the plaudits of the most avid aficionados yet a knockout communes directly with the soul of the most casual fan. Violently abrupt, visceral and uncompromising the knockout is boxing’s most enduring trump card.

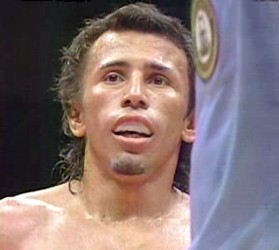

Edwin Valero, throughout his seven-year professional career, has made a habit of knocking out those placed in front of him in a boxing ring. Twenty five times in succession the 27-year-old Venezuelan southpaw has brought about the cessation of his night’s work in abrupt fashion. At 25-0 (25) he stands on the cusp of the big time. Boxing’s only reigning world champion with a perfect knockout record, he is the former WBA Super-Featherweight titleholder and following his brutal stoppage of Antonio Pitalua in April, the incumbent WBC king at 135 pounds.

Let us take a moment to chronicle Valero’s professional achievements before analysing their relative merits. A world champion in two weight divisions. The former holder of the world record for consecutive first round stoppages; his first eighteen fights all ended inside three minutes, an achievement that on the face of it makes even the early efforts of such noted bombers as Mike Tyson and Thomas Hearns look positively slothful. Valero made four successful defences of his 130-pound title (all by stoppage) before moving up in weight to contest the title vacated by Manny Pacquiao.

Valero, despite having fought only twice in America has become something a darling of the hard core boxing community. His commitment to attack regularly borders on the reckless and he guarantees excitement from the opening bell; which in itself is not something that a number of his fellow world titleholders can claim. Yet for all the glossy perfection of his record many respected commentators believe that there is a considerable quantity of dross to be found amidst the gold when panning through his ring record.

For starters the quality of Valero’s early career opposition has been at best questionable at worst risibly inept. The combined records of his first eighteen opponents stood at 62-94-17. This suggests an unbroken litany of mismatches that make the early career progression of most prospects look like a series of herculean endeavours. Critics of a satirically unsympathetic bent have argued that the only credentials one requires to face Valero is a steady heartbeat and a clean pair of gloves. Of those eighteen opponents only nine possessed a winning record, while five of them had never won a professional fight. Some of this matchmaking borders on the criminally negligent. Indeed, what the management of one Thomas Zambrano, 0-4, were thinking in sacrificing their man to a rising Valero (at that point with 11 successive first round stoppages to his credit) may forever remain a mystery. Obviously the boxing norm where promising prospects are concerned is to provide them with a gently rising learning curve. However, even the most cursory glance at Valero’s record highlights that his early career represents more of a flat line than an arc. Still a boxer can only dispatch the opposition placed in front of him and to his credit he has done so impressively and with a minimum of fuss. Mike Tyson was viewed as relatively untested and the quality of his opposition called into question before his 1986 challenge for Trevor Berbick’s WBC Heavyweight belt; having feasted on the likes of Hector Mercedes, Trent Singleton and Larry Sims throughout the infancy of his nascent professional career. When all was said and done the real opponents bowed before the fury of Tyson’s fists when the bigger challenges were presented to him. Who is to say that this will not be the case with Valero?

In rising to the top in his division Valero has certainly had to overcome adversity. On February 5th 2001, while still competing as an amateur, Edwin was involved in a serious motorcycle accident. He fractured his skull and required an operation to remove a blood clot. This delayed the start of his professional career and has subsequently presented him with a variety of stumbling blocks as his career has progressed. Having been cleared to box by a Venezuelan doctor in 2002 Edwin appeared to have put his near death experience behind him. His exciting style and eye-catching knockout run saw him signed up by Golden Boy Promotions. His joy was short lived as a failed MRI scan in January 2004 in New York put paid to any hopes he had of making a name for himself in the United States.

Forced out of action until May 2005, when he resumed his career Valero became something of a rootless traveller, fighting in Panama, Argentina, France and his native Venezuela before making something of a second home in Japan. After capturing Vicente Mosquera’s WBA Super-featherweight crown in Panama, in his 20th fight and despite only ever having been extended to the second round once, Valero made three of his four title defences in Tokyo. Curiously two of the aforementioned defences were against mediocre Japanese opposition. Even as a champion Valero, it was argued, was gorging on easy marks. The feather fisted Nobuhitu Honmo was 25-4-2 (5) and hardly a threatening first defence. While thirty six year old Takehiro Shimada, 22-3-1 (16) had “earned” his title shot with three tune up wins over novices with a combined 4-4-1 record. While these figures highlight the paucity of quality opposition on the records of both Valero and his challengers maybe the real fault lies with the alphabet organisation that sanctioned these title matches.

That Valero is popular and extremely fun to watch is unquestionable. His bouts on You Tube feature countless hits. He throws punches in bunches and stalks his opponents with an intensity that many top fighters will certainly find troublesome. Certainly his last opponent, Antonio Pitalua, never new what hit him in their recent title bout. However, his crudity is evident on even a brief viewing. His shots are often swung rhythmically from the shoulders in looping parabolas and he appears to disdain the use of the jab almost as a matter of course. While swinging his big shots he often appears alarmingly open. Indeed Mosquera, after surviving the early round onslaught managed to drop Valero with a neat counter in the third round. However, the fact that Valero dusted himself off and roared back to stop the defending champion speaks well of his powers of recovery.

Valero appears to rely solely on his concussive power and it remains to be seen whether he is sufficiently adaptable to be able to change mid fight against an opponent who can withstand his punches and fire back. Punchers, while the opposition so regularly acquiesce to defeat, often begin to consider themselves unbeatable. Why change, the reasoning goes, when what you are doing works and in Valero’s case, works so spectacularly. Edwin’s management team need only to take a look at boxing history to discern the answer to this question. There will come a time, possibily in the very near future should Valero secure the match against Manny Pacquiao that he has been clamouring for recently, when an opponent either proves elusive enough to avoid the Venezuelan’s rushes or resilient enough to withstand his punches. When this moment arrives and it will, of that there can be little doubt, what will Valero have to fall back on?

In rising to the top despite not having faced any truly challenging opponents Valero may have failed to lay the firm foundations necessary for continued longevity at championship level. He has never had to survive the gut-wrenching trauma that many prospects overcome on their way to the top. He has not needed to rebound from a potentially fight ending cut or rise (the Mosquera fight aside) from a knockdown against an opponent equal to himself in both skill and desire. He has not been required to display the sort of guile or resourcefulness that he may well need to overcome the very best boxers in his division. I stress the word “may” as in many contests his howitzer like left hand will render the ability of his opponent meaningless. He does appear to hit hard enough to hurt anyone he can tag. While it is not impossible to imagine the likes of Nate Campbell, Juan Diaz, Paulus Moses and even Juan Manuel Marquez succumbing to his swarming attack, none of them are likely to go easily, early or without ferocious argument.

Valero has been quoted as saying he only wants the biggest (and thus most lucrative) fights available. His preferred opponent of choice (no surprises) is the pound for pound king Manny Pacquiao. In taking this stance Edwin may be shortening his spell at the very top. A fight with Pacquiao, who figures to be around for quite some time to come, will be much more of an attraction should Valero defeat some legitimate championship opposition in the interim. In racing towards such a potentially apocalyptic confrontation Valero may be exhibiting hubris of the sort that could derail what could well turn out to be a stellar career.

If, as sadly looks to be the case, his July bout with Colombian banger Brieidis Prescott, 21-0 (18) has indeed been cancelled, then Edwin has missed a chance to put himself in the shop window and in doing so showcase his power and ferocity for a worldwide audience. The fight was a guaranteed thriller. The 5’11’’ power hitter who annihilated Amir Khan in 54 seconds last year in Manchester would have come straight at the champion, allowing to him to prove his metal and potentially secure a sensational win. That the match was both fraught with danger and harboured the possibility of defeat for Valero may have had some bearing on its cancellation. Though, in defence of Valero he has certainly talked the talk in recent months and claims to be willing to fight anyone.

Edwin would clearly benefit from the sort of expert schooling one of the top trainers could provide him with. If he could shorten up his punches, exhibit some variety and polish his defence skills then we would have the makings of a potentially formidable fighter. Ray Arcel managed to turn the trick on another raw young slugger way back in the late 1960’s and no one can doubt that one Roberto Duran managed to repay his investment with two decades of championship excellence. Crude power alone, while it may be enough to win you a brief moment of fleeting repose at the championship summit, will rarely afford you a prolonged sojourn at the very top. Still, whatever happens promises to be fun while it lasts and who is to really say at this juncture how long the ride will go on? Edwin Valero is an uncompromising fighter, who has battled against the vagaries of fate and misfortune to reach where he is today. He may be wild, but he is certainly dangerous. To my mind there is more than a touch of Pipino Cuevas in the Venezuelan’s style and approach to combat. Pipino, whose crudity was equalled only by his ferocity and punching power, dispensed a four-year reign of terror over the Welterweight division. Who is to say that, possessed of the proper schooling and with some more valuable experience under his belt, Edwin Valero cannot go on to do the same. I will certainly continue to enjoy watching him try.

Comments are closed.