By Jay McIntyre: The “Blast From The Past” series is meant to harken back and remind us of some of the great fights and fighters of days gone by. This particular installment gives Joe Louis and Max Schmeling the attention they deserve. For the full-length article and its accompanying visual aids, please go to: http://a-neutral-corner.blogspot.ca/2014/06/blast-from-past-louis-vs-schmeling-i.html

By Jay McIntyre: The “Blast From The Past” series is meant to harken back and remind us of some of the great fights and fighters of days gone by. This particular installment gives Joe Louis and Max Schmeling the attention they deserve. For the full-length article and its accompanying visual aids, please go to: http://a-neutral-corner.blogspot.ca/2014/06/blast-from-past-louis-vs-schmeling-i.html

When can a single fight mean more than two men punching each other in the face?

In an age as politically charged, and economically deflated as the 1930’s a single boxing match could represent a whole lot more than two men trading knuckles. The 1930’s were different times, sandwiched between the two World Wars and following the decade of decadence that was the “Roaring Twenties”. In the 1920’s, people had money and they spent it. Athletes like Jack Dempsey and Babe Ruth were giants among men, paid astonishing wages to achieve their astonishing feats. For the middle class, investing in the stocks of nebulous companies that no one knew too much about was in vogue. This was okay, because everyone was doing all right – and when times are alright, the mistakes we make don’t seem all that bad. But clouds were forming on the horizon, and these clouds were the purchasing of stocks with borrowed money – “buying on the margin”.

And then -suddenly – the Great Depression descended like a tired sheet of fog and smothered the once brilliant lights and glamor of post-war largess. The timing was apparently random, and its tenure an apparent eternity.

Meanwhile, desperately insecure and naively young political ideologies sought to answer the daily woes of the common man (and woman). The truth, however, was that there was no quick fix to this interminable suffering. No one had an answer, and most stopped trying to look for one. You’d be surprised what a person can get used to when they lose hope. In front of this despondent backdrop, some things kept gamely moving forward – and one of those things was boxing. Gone were the long-reigning champions and a new mixture of fighters emerged during the 1930’s. Jack Dempsey was gone, as was his conqueror Gene Tunney. In their stead was a de facto tournament meant to sort out the best of the best. Max Schmeling, Jack Sharkey, Primo Carnera, Max Baer, James J. Braddock, and Joe Louis took turns as champions, but it wasn’t until Schmeling and Louis fought in 1936 that a boxing match – politically – became so much more.

When a white German fighting out of a Fascist European state was poised to fight a black American from a democratic and capitalist state, one would be hard-pressed to find a greater contrast in the world at this time. Louis-Schmeling I, despite the intentions of the two boxers involved, was meant to demonstrate the supremacy of two ideologies – fascism and democracy. Their first fight in 1936 was closely contested, and since this was an age when the best did indeed fight the best on a consistent (though not unanimous) basis, it was no surprise to see a rematch in 1938.

Let’s turn back the clock and appreciate a moment (or, rather two moments) in time quite unlike any other.

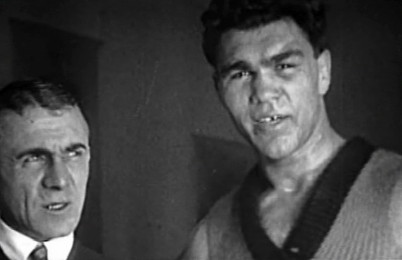

The Fighters:

Joe Louis

At 6’1″ and just under 200 lbs at his peak, Joe Louis was a sizable heavyweight by pre-1960 standards. His footwork made him look bored and his face had a look of disinterest that verged on apathy. He was shy and shrank from the spotlight of the public. Such aloofness could be perceived as weakness. And yet this man was perhaps one of the most fearsome and explosive boxers to ever step through the ropes. Joe Louis coupled a well-rounded style with a patient ferocity that culminated in an unprecedented twenty-five defenses of the world heavyweight championship. No one has ever duplicated such an impressive string of defenses, and although the caliber of his opponents was not always something to brag about (hence the “Bum of the Month Club”), his dominance over the upper crust of the division lends itself to the credibility of his legacy.

Fighting out of the “Blackburn Crouch”, Joe Louis stalked his opponents. Louis carried his head is slightly to his right. The weight is over his right leg more than his left. His right hand is used to catch and parry labs, or block left hooks, while his left shoulder is used to roll any attacks from his opponent’s right hand.

His lead foot was usually pointed towards his target’s centre so that his own jab has a clear line of attack. His jab also fired upward from a lower angle (as opposed to from shoulder height). His knees are usually bent, and this allows him to torque his body weight into his punches. His centre of gravity is also little lower, which means his jab can flick upward from a blind angle. Defensively, Louis used his stance to negate the probability of being hit (as stated above, his right glove catches his opponent’s lefts, while his left shoulder catches his opponent’s rights), and he rarely allowed his opponent to get off more than one shot. Often, his countering was a big part of his effective defense as he would catch or roll an incoming shot and then respond before they could establish much of an offense.

Prior to his fight against Schmeling, Louis was undefeated and was earning a reputation as a knockout artist on his way to becoming the number one contender. But before he became world champion he had some hard lessons to learn. A fighter can continue winning while making mistakes and no one will be the wiser until a worthy adversary arrives and exposes that fighter’s weakness. Max Schmeling was Joe Louis’ worthy adversary, and he handed him an important loss early in his career.

Max Schmeling

While Schmeling was the perfect foil for Louis in many ways, he was widely condemned as an easy fight for the American and there were several reasons for this. At age 30, Max Schmeling was by no means old or past his prime – even by boxing standards – but he was never an unstoppable force like Dempsey before him, or Louis after him. Winning the Heavyweight title in 1930 when Jack Sharkey was disqualified for too many low blows, Schmeling would only defend the title once over the next two years again Young Stribling before losing it to Sharkey in a very even rematch in 1932. He later was also knocked out by Max Baer in the tenth round when they fought in 1933.

When he first fought Louis in 1936, he was a well-known name – a scalp that would look good tucked into the belt of a conqueror on the warpath. He was a very good fighter, but never the greatest among a cadre of dangerous men. In fact, by the time Schmeling was first scheduled to fight Louis in 1936, it had been four years since he won a fight in the United States, and that victory came over Mickey Walker – an upstart middleweight that swelled up to heavyweight to try and make a name for himself.

Despite some big losses, perhaps the worst thing to happen to Schmeling was the unfortunate timing of being a German at a time when Germany was throttled in the grip of Nazism. While it is obvious that many Germans disputed Nazi policy one thing they could all come together and see eye-to-eye on was the matter of national pride. You have to remember that Germany felt shamed and embarrassed by the oppressive clauses of the Versailles Treaty which stripped her of her economic and military might (while also laying nearly all the blame of the Great War on her tired shoulders). Their national pride was stung. The Nazis on the other hand were always eager to pounce on opportunities that demonstrated dominance, and felt that Schmeling could be their poster-boy – their Uber-Mensch – who could showcase German superiority on a world stage. As such, both Germans and German-Nazis clamoured for Schmeling’s success for different reasons.

In looking at Schmeling’s stance, one thing that instantly becomes obvious when comparing it to Louis’ is his more upright posture. This is a more classic stance for boxers during this time. He could use his rear foot as his “rudder” to steer himself around in order to find his opponent’s centre, while moving in a balanced manner to respond either defensively or offensively. He also kept a wider stance and used his lead foot to gauge how close he was to his opponent’s lead foot. Typically the jab is used as the measuring stick of most fighters, but foot placement can subtly get the job done as well.

In the eyes of many an observer, what could this “has been”, and “washed up, Nazi puppet” do to stop a fighter that Ernest Hemingway once referred to as a “the most beautiful fighting machine [he had] ever seen”?

First Contact – June 19th, 1936 at Madison Square Garden

It is fitting that the venue for their first altercation would take place at Madison Square Garden which would also later become the site of one of the largest Anti-Nazi rallies in the United States. Although Schmeling had little sympathy towards the prevailing rulers of his country, he nonetheless became an unwilling symbol of Nazism due to his German nationality. Joe Louis was the first prominent black heavyweight since Jack Johnson, and fought for a country that was quite opposed to the ideals of the Nazi regime. Boxing rivalries are at their best when two fighters assume the roles of good guy and bad guy. At face value, boxing fans received just that.

Title fights back then were scheduled for fifteen rounds, but this chess match wouldn’t go the distance. Many wrote off Schmeling as an over the hill fighter based on a series of defeats like his 10th round KO loss to Max Baer, but Schmeling was easily the most complete fighter Louis had faced at that point in time. Both men brought a very dynamic skill set to the table and both men were at a crossroads in their respective career.

In this particular fight Louis boxed patiently and this gave Schmeling far too many opportunities to size him up. Schmeling was a cagey veteran that had seen it all in the ring and he used the breathing room which Louis afforded him to compute the movements of his opponent and forge a successful plan of attack. Schmeling knew his adversary was a dangerous combination puncher so he fought smarter as the fight wore on.

When Schmeling did lead, he often wouldn’t let himself get carried away. He would throw a punch or two and then cover up or get out of trouble. This was a wise idea as Louis was both potent and swift in the use of his combinations. By reacting defensively after punching he denied Louis the opportunity to punish him. He also chose to use the jab for basically everything except to cause damage. Knowing that he couldn’t trade jabs with Louis, he instead pawed with it to gauge distance and draw the jab of Louis. When thrown across the jab of one’s opponent the right hand is referred to as a ‘cross counter’ as it crosses the opponent’s arm, and Schmeling’s cross counter right proved to be decisive.

Perhaps the greatest flaw in Louis’ game was his tendency to drop his lead hand after jabbing gave the shrewd Schmeling an opening which he would exploit time and again. The punch of this fight – which was a remarkably enjoyable one fought at both close and long range – was Schmeling’s right hand. Time and again it found its mark and there were a variety of reasons for its success.

Schmeling had his number.

Upon being counted out, Louis remained on the horizontal and Schmeling rushed over to help him up. The sportsmanship and respect was incredible. The animosity that apparently existed in their punches did not exist in their evaluation of one another as human beings. Although the world was on its way to turmoil, the perspectives these two men were forced to represent did not infiltrate their evaluations of one another.

Apparently Schmeling had a lot more to offer Joe Louis than many had given him credit for. It was a perfect performance on the perfect night and became a career defining victory for the prizefighter than many referred to as a “has been”.

The Rematch – June 22nd, 1938 at Yankee Stadium

The rematch couldn’t have been more different than its predecessor. As tensions rose across the globe, so did the anticipation for this rematch. Rather than a protracted battle, the sequel was a one round beat down. Things picked up exactly where they left off and there was very little in the way of a feeling out process. One of Louis’ mistakes the first time was giving a cagey veteran like Schmeling the chance to box and process Louis’ style. This time around, Louis attacked with greater pressure, first double-jabbing inside and getting to work with power punches, and then later, leading with a left hook to get inside (Schmeling placed his glove in front of his face to anticipate more jabs and was caught by the left hook). He refused to let Schmeling’s right hand find the success that it had two years before.

After this, he stood just outside the range of Schmeling’s right hand and waited for him to lead, catching him as he closed the gap. Backing Schmeling close to the ropes, Schmeling shelled up and waited to counter Louis as they both stand in the phone booth. The fight ending combination was a slow, methodical one beginning with a right uppercut as Schmeling crouched forward. Once he was stunned, Louis smelled blood in the water and wouldn’t let up, alternating rights and lefts to the head and body as Schmeling slowly wilted. Fittingly enough, it was a right hand that ended this fight. The very same punch that proved so troublesome for Louis two years before.

Schmeling is a very capable defender that was at the mercy of Louis who could punch fast (as was seen in frames 2 and 3), and also uses punches to leverage openings in Schmeling’s defense. Louis could be patient when he needed to be, and on many occasions you could see Louis line up his shots, or wait for an opportunity to make the most of his offense.

This fight showcased Joe Louis when he was in peak form, while Max Schmeling was perhaps not the same fighter he was two years before. Between their first fight in 1936 and their rematch in 1938, Louis fought eleven times (winning the heavyweight title from James J. Braddock in 1937), while Schmeling fought only three times. Long layoffs between fights can dull a fighter’s edge and this had been apparent when Jack Dempsey took three years off before losing his crown to Gene Tunney in 1926, and more recently when Mikkel Kessler lost a rematch to Carl Froch in 2013 (Kessler fought three times against average competition between his 2010 and 2013, while Froch fought five times against much stiffer competition).

Aftermath

It’s a fascinating thing when art imitates life, and even more thought-provoking when the actions of a few, serve to be an unintended microcosm for the actions of many. Schmeling’s initial victory and overwhelming triumph over Louis served to foreshadow the initial onslaught and success of Nazi Germany years later during the Second World War (Sept. 1st, 1930 – Aug. 8th, 1945). Once adjustments were made, however, Louis struck back with a vengeance and ended the dispute once and for all. This is not altogether different from the rallying and eventual success of the Allies during the last half of the war. Louis, like America, would go on to unprecedented success and dominance as a world champion, while Schmeling would return to Germany and box with a record of 4-2 over the next decade before retiring. An unceremonious ending to a once powerful figure.

This is where the parallels come to an end. Following his loss, Schmeling was stripped of his wealth by the Nazis and left destitute. It wasn’t until after the war that Schmeling – an opportunist in and out of the ring – was able to rebuild his lost wealth through work with Coca Cola in post-war Germany. Eventually he owned his own bottling plant and made a fortune. Joe Louis exited the war with massive debts and owed a great deal in taxes. His finances had been mismanaged and the once mighty conqueror was forced to return to the ring as a faded version of his former self to pay $500,000 in back taxes to the IRS. Of the 4.6 million dollars he made during his entire fighting career, he barely saw 17% of that due to the irresponsible control of his parasitic managers.

But all was not lost. The respect that was forged in the ring in 1936 and 1938 echoed for the rest of their lives as Schmeling saw in his one-time conqueror a friend in need. Assisting in the payment of his taxes, Schmeling (among other contributors) sought to help out Louis whose accumulated interest from taxes caused his debt to rise to one million dollars by the end of the 1950’s. Although Louis was able to find a more comfortable existence later in life through a payment plan agreed upon by the government, it was Schmeling who helped to pay for Louis’ funeral costs when he died in 1981 (he also acted as one of the pall-bearers).

Both men survived the Great Depression, the Second World War, and each other. The animosity between the countries they sought to represent did not infect their rivalry. Instead, rivalry turned to respect. A respect that was found in the most remarkable of circumstances, and lasted a lifetime.

Comments are closed.